An Interview With Montreal Graffiti Artist Zola

The Link Caught Up With the Artist Zola, Known For Her Depiction of Black Bloc

You might have seen Zola’s characters pasted onto Hochelaga’s laneways, or maybe you’ve seen them on banners at protests.

The Link caught up with the artist in her studio to learn more about her politics and what inspires her art.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What did your wheatpaste art look like at first? What style were you going for?

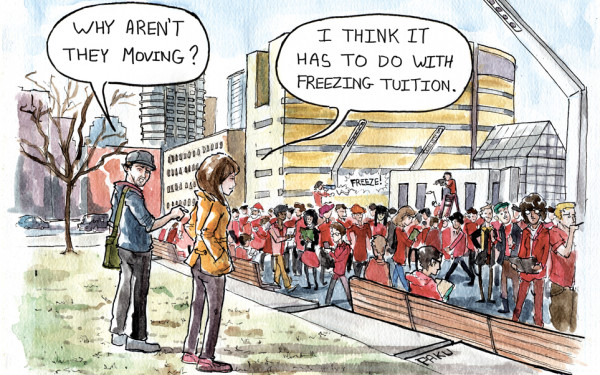

Right away I focused on representing anonymous protesters and black-bloc, as well as gender non-conforming people, or female and femme people, because people stereotypically think of, you know, that skinny white guy that’s throwing rocks at windows. But in reality black-blocs during the 2012 strikes were full of women and queer people, who were also doing a lot of defensive work and care. But that was just not recognized or seen.

What about wheatpasting is attractive to you?

It’s the fact that you can do whatever you want, and the point of doing street art is also to take back space. It’s a political act, I see it as direct action. Everything I do is illegal and I don’t ask permission. I’m saying, ‘This is ours and there should be room for us to take up space here and claim territory against capitalism.’”

Does your art aim to challenge the machismo often associated with black-bloc tactics?

Yeah totally, and also there’s the anarchist black-bloc communities that really needed to have feminism brought to their attention.

There’s also the street art world, that’s kind of weird because most street artists are men, but there’s a lot of other types of folks, queer and women, but they don’t get as much visibility.

“The point of doing street art is also to take back space. It’s a political act, I see it as direct action,” Zola.

The people that you put up, are most of them your friends?

Some are photos of peoples at protests I find through news websites, especially ones that have happened in Montreal. I’d also take pictures at demonstrations and create characters from that. So I kind of knew the people, but not personally at first. I also do photoshoots with my friends, so a lot of the pieces are my friends.

The people that you use as your characters, what causes are they usually involved with?

It’s really directly related to what I’m involved in politically, so it started out with the student strikes in 2012 and it grew into just anarchism and anti-capitalism generally. And recently yeah, there’s been a lot of anti-fascist work done around the city, so that also shows up.

People are really on the edge about that and so my stuff gets trashed down or covered really, really fast when there’s a hint of anti-fascism so I have to hide them if I want them to stay up.

I wanted to learn about the postering you did you raise awareness the police shooting and killing of Fredy Villanueva, which happened 10 years ago in Montreal-North.

I got involved with the committee supporting the Villanueva family. They had been asking for ten years to have a mural or visual representation of Fredy there and the city had refused it.

There was a glimpse of hope last year because the new mayor seemed interested and then afterwards the neighbourhood’s mayor said the park was going to be all changed (in a way to mark his death), but there was not going to be any mural or mention of Fredy. That was a really big hit to the family and that’s the period where I started being involved.

We decided we could find other ways to make Fredy visible in the neighbourhood even if the city is not going to commission a mural. So we did it on our own.

It was to remind people that the ten year anniversary was coming up but also it was an act of liberation in saying, ‘He’s part of the neighbourhood and he will never be forgotten.’”

It was really powerful to do that and to have a lot of people come back and say that they would talk about it with their kids because they saw the posters and they were touched by seeing him around.

What is the effect that you want to have on people who see your art?

I just want people to always be aware of the presence of radical politics. I want people to know there’s people out there fighting against capitalism and that they’re not just accepting the status quo and that there are ways to resist and to build alternatives and be part of activist projects.

Correction: The online subhead in a previous iteration of this article stated that Zola was known for her depiction of women in hijabs. In fact, her work depicts people dressed in Black Bloc. The Link regrets this error.