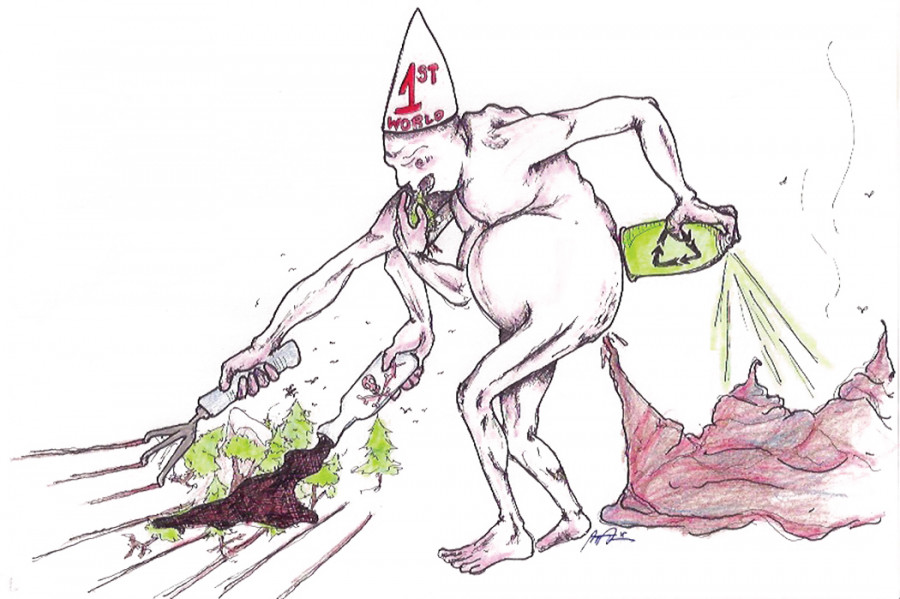

These Problems are Garbage

Trying to Solve Big Problems With Little Soutions

Controversy arose over the city dumping billions of litres of raw sewage into the St. Lawrence river, but the growing issue of waste management wasn’t discussed, though it runs deeper than any contaminated riverbed.

Humans, especially in developed countries, generate more garbage than we can dump, bury, or recycle.

Canada is the second largest country in the world, offering a wealth of natural resources most people only see as processed plastics and metals. But for all of this natural wealth, our environmental protection policies are lacking if they permit the hurried discharge of waste back into the fragile watershed.

We are world leaders in individual garbage production and one of the greatest exploiters on the entire planet, according to the Conference Board of Canada, an independent not-for-profit organization.

More bad news; we’ve got failing grades in most, if not all, of our environmental policies, according to the Pembina Institute and Canada’s Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, who assists the Auditor General in environmental affairs. Are you con- cerned? Because what’s worse is that not many people seem to be.

Our individual consumption rates have actually been steadily increasing, according to the Conference Board of Canada. As our landfills overflow, “single-use convenience” has been gaining traction in households—everything from Keurig pods to disinfectant wipes are produced, consumed, and tossed out in a hysteric hurry, but the recycling process is never fast enough.

According to Forbes, garbage has become America’s main export, and Canada is no better, having dumped 50 containers of garbage in the port of Manila in the Philippines almost two years ago.

Thankfully, recycling has long been part of waste management and self-preservation strategies for cities. Since the 1990s, recycling has become a social norm, and more advanced technologies make it easier to process some kinds of waste.

In 2004, while 73 per cent of all waste in Canada went to landfills, the rest was diverted to recycling, composting, and other repurposing strategies, according to StatsCan. More and more people are recycling, so at this steady pace of growth, we can expect to see all of our garbage recycled and back in our hands in no time. Right?

Except for one detail. Our lust for convenient commodities grinds out a never-ending series of packaging innovations, which prolong shelf life, make the frozen foods stand up without support, and ensure durability during long voyage from factory to Pharmaprix.

Most of these packaging innovations are made of layers of metal, plastic and paper which make them hard to sort and recycle, or glass, which has always involved a cumbersome and inefficient recycling process, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

On top of that, our inflating dependence on plastic and its millions of equally toxic derivatives has a large negative environmental impact.

A study conducted by the Cambridge-MIT Institute analyzed the energy consumed during the extraction, production and transportation of a material, compared to the potential energy that could be received during the recycling program (after factoring in the energy costs of the recovery process itself). The study found that plastic consumed up to four times as much energy in its production than could be recovered at the end of its life cycle.

Humans, especially in developed countries, generate more garbage than we can dump, bury, or recycle.

Along with the economic blows the recycling industry is feeling as raw materials like plastic become cheaper to extract, recycling becomes a harder pitch to sell.

The more we examine the life-cycle of a product, the more we realize that our overconsumption can’t be remedied with efficient waste disposal alone, as told in Annie Leonard’s animated documentary, The Story of Stuff.

The problem is multilevelled, from extraction to disposal. Recycling is just one piece of the “reduce, reuse, recycle” solution. The first, and most overlooked, is REDUCE.

Growing global consumption is unsustainable, not only because its demand for toxic synthetic chemicals is harmful to our health, but also because the Earth simply doesn’t have enough natural resources to accommodate the Western ideal of the “developed world” for every country.

To live within the means of the Earth’s resources, our “Ecological Footprint” would have to be 1.7 global hectares per person, which is a measurement of how much the planet and atmosphere can clean up after us, according to the Global Footprint Network, a non-profit think tank.

As it stands, Canada and America’s footprints are nearly seven global hectares per person.

Our economy is based on the fast import of new and cheap materials, and the primary export of garbage for other countries to deal with.

Where will “away” be when these other countries finally “develop” to the American level and have to throw away their garbage too?

When our provincial government declared that dumping our waste into the river was our “only solution,” they weren’t being honest. Taking a dump in the St. Lawrence river is our only easy solution.

Instead of developing efficient waste disposal methods to accommodate our lifestyles, we need to start accommodating our lifestyle to the limited resources of the planet.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)