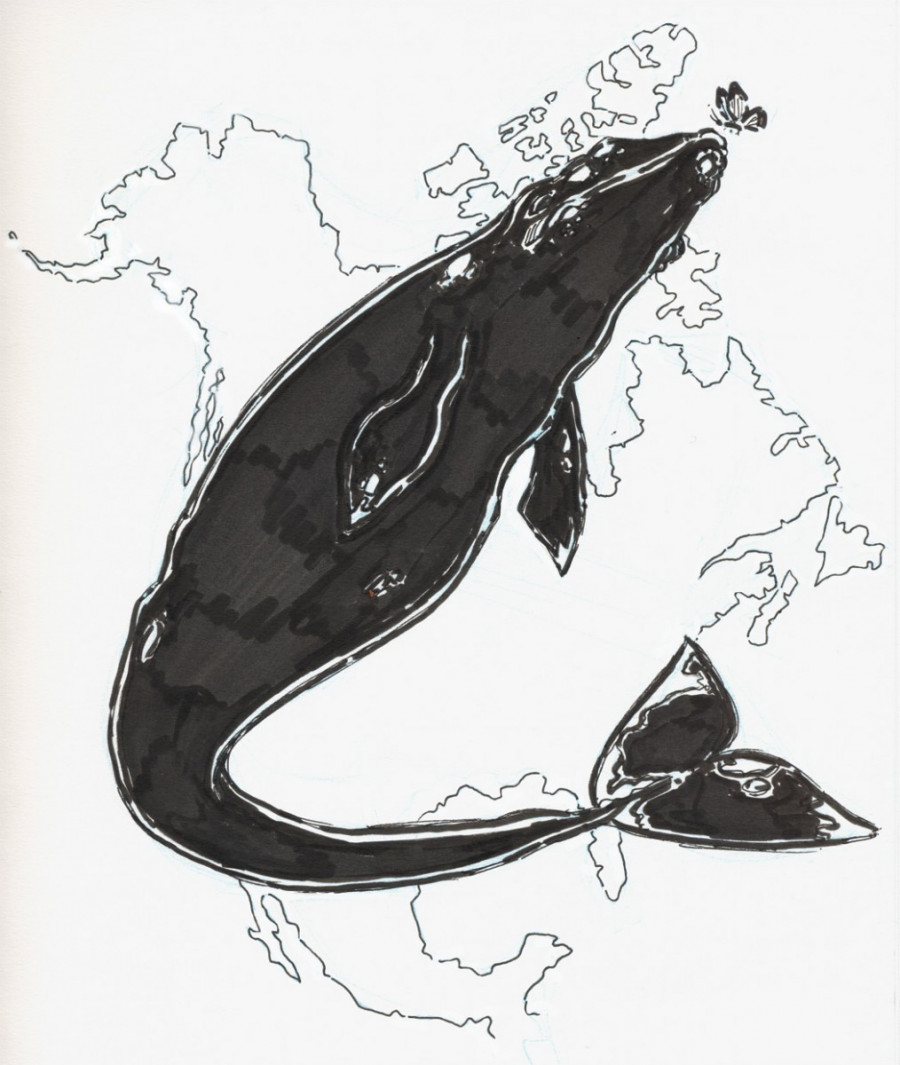

The Monarch Butterfly, the Gray Whale and the Free Trade Agreement

Tearing Down Borders for Environmental Solutions

Canada, the U.S. and Mexico share a lot. While borders divide North America, free trade agreements from the 1990s allow products and resources to move easily through them. Shared environmental governance, on the other hand, is still in the works.

When the North American Free Trade Agreement was written up, an environmental agreement was created to go along with it. Officially it’s known as the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation and its watchdog, the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, is based in Montreal.

But this environmental watchdog has been blocked by Canada and its free trade partners in the past few years.

The latest case was a recommendation by the CEC Secretariat to look into Alberta tailings ponds. The tailings ponds hold waste that’s left over when oil is extracted.

A submission was filed over a year ago with concerns that the tailings ponds were breaking Canada’s Fisheries Act. The tailings pond, it claimed, was leaking into the nearby Athabasca River and creeks in Northern Alberta.

The submission didn’t pass because a similar complaint was filed in court, but that case was dismissed long before the secretariat was turned down.“Normally it doesn’t work like that,” said Hugh Benevides from the CEC. Secretariat recommendations usually suggest there’s enough material for an investigation and the council votes along with the secretariat.

The Alberta tailings pond recommendation from the secretariat is the fifth to be rejected by the council since 1994—three of them were in 2014 and 2015.

The other two rejected recommendations hoped to investigate Canada’s polar bear protection and B.C. salmon farms.

“The process is supposed to be transparent,” Benevides said. “You’d be shining a light on how the system works.

“In this situation, the public’s not really getting that because the council voted against getting to the end result,” he said.

These issues will likely be brought up at next week’s Symposium on North American Environmental Governance, hosted by the Loyola Sustainability Research Centre.

The roundtables will feature the executive director of the CEC’s secretariat Irasema Coronado, president of the International Institute for Sustainable Development Scott Vaughan and executive secretary of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity Braulio Dias.

All of these international organizations are based in Canada—the UN Convention on Biological Diversity secretariat is in downtown Montreal.

A representative from Central America and the Dominican Republic free trade agreement will also be there to “compare notes” on their processes, Benevides said.

The symposium will highlight the publication of a book series called Environmental Governance: Local-Regional-Global Interactions by Loyola Sustainability Research Centre director Peter Stoett and University of Texas-Pan American assistant professor Owen Temby.

The series will focus on transnational environmental governance and feature experts on biodiversity, invasive species and energy.

Scholars will come together to discuss environmental policies and issues on handling oil and shale gas, biodiversity and conservation.

“It’s a controversial moment in the history of Canada’s relationship with the CEC,” said Stoett.

“[Environmental policy] got distilled in this debate over a pipeline,” he said. The Canadian government is being accused of leaving environmental issues behind in its promotion of the Keystone XL pipeline.

Stoett says Canada has a harmonious relationship with the U.S. and Mexico regarding environmental issues. As climate change increases the stress on natural resources, those relationships will be challenged.

Tri-national institutions will need to help manage that rough terrain, and they need to be effective, he said.

“Right now we’re all over the place and we have to come closer together,” Stoett said. “None of these countries will solve these problems on their own.”

Policy coordination will have to confront the Great Lakes drying up while the coasts risk flooding. All the while invasive species move north as the climate becomes more temperate.

Stoett says North America needs a common standard of wildlife conservation.

That way when species like the monarch butterfly and the gray whale migrate across the borders of all three countries, governments will know how to protect them.

“Right now we’re all over the place and we have to come closer together. None of these countries will solve these problems on their own.”— Peter Stoett, Director at the Loyola Sustainability Research Centre

The CEC, Explained.

The CEC has two branches. The Secretariat analyzes claims submitted by citizens or organizations. The claims should prove a country isn’t enforcing environment laws.

If they fit the requirements, submissions get recommended to the CEC’s council. The council is made up of environmental officials from each country rather than an independent body.

Since the CEC was created only 83 submissions have been filed—20 of them resulted in “factual records,” produced by the secretariat with council approval.

Submissions will not always result in a factual record if they don’t meet the requirements, or if the implicated government can provide a response or remedy. They usually deal with issues concerning migratory birds, endangered species, forestry and mining.

Canada, Mexico and the U.S. created the NAAEC to work on environmental issues that touch the three countries, specifically the issues linked to free trade.

But the CEC has grown so that it can study cases not directly linked to trade.

“We’re looking at the environmental stuff, no matter how it arises,” said Benevides from the CEC.

But it isn’t a legal body and doesn’t enforce environmental laws.

“The public can do whatever they like with it, but it’s often to raise awareness or pass that factual record onto others,” Benevides said.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)