The Beloved Island

Two Architects, a Landscape Architect and a Historian of Montreal Talk About Their Favourite Spaces in the City

Ste. Catherine St.

Antonin Labossière, Architect // Rayside Labossière

WHY IT’S SPECIAL

“For everything it represents. The fact that it crosses through the city from east to west and from west to east, its variations, the changes in the type of commercial activity, the changes in general feeling. It’s what’s most evocative [about] the city of Montreal. Its design is a juxtaposition of many different elements, of different times, different styles and different purposes.”

HOW IT INFLUENCES HIS WORK

“In architecture and urban planning, we often forget to see things as evolving. [But] a precise moment of design or urban planning won’t succeed in truly determining or influencing behaviour. You can plan, but not all that much. The economic aspect [of Ste. Catherine St.] is important, [but] in order for it to be an economic hub, people need to want to go there, so it has to be very social. There are a lot of ingredients [and] we don’t necessarily have the recipe for all those ingredients, [but] when we see them, we should take advantage of them and make the most of them.”

ITS FUTURE

“We need to make it possible for [the street] to be made pedestrian-only one day; I think that would certainly improve it. We shouldn’t become stuck in time by saying that cars are vital.”

St. Viateur St.

Claude Cormier, Landscape Architect // Claude Cormier + Associés

WHY IT’S SPECIAL

“It feels real—it feels like real Montreal. It’s not pretty, but it’s a kind of a different type of beauty: real, cool, relaxed, urban and sexy. That’s the Montreal that I like. There’s a feeling of real life in it. It seems a little secluded as well, because the subway doesn’t go there. You have everything in that street. All kinds of foods… You have coffee shops, you have little bars, you have cafés, rotisseries, flower shops, key places, some clothing. It’s a real village.”

ITS SOCIAL SIDE

“People and the way they interact among themselves, with different races, age groups, milieux… I don’t sense friction and tension and I just find there’s a very nice flow of positive urbanity. It’s the Montreal that I like very much. I feel that people are tolerant—that’s my perception—maybe not—but there’s kind of a sense of live and let live. The traffic and the pedestrians, the bikes, they deal with each other beautifully. It’s not, ‘you have a car, you’re bad.’ I think it’s the place that makes people that way.”

WHY IT DOESN’T NEED A PROFESSIONAL

“It was not made, it was not created at all. But it just grew into that. We get sick of design. I do! I get sick of design that has no soul and it’s more of a stylistic thing—everything gets flat, everything starts to look the same. I kinda like the contrast. Enough of this sameness! Sometimes anti-design is good.”

Parc de L’Île de la Visitation

Paul-André Linteau, Historian // UQAM

WHY IT’S SPECIAL

“It’s a magical spot on the bank of Rivière des Praries. There are a lot of birds, and a lot of Montrealers who come to relax and enjoy the space. It’s a really interesting natural landscape.”

ITS HISTORICAL SIGNIFIGANCE

“It’s on the site of Sault-au-Recollet, one of the first villages established on the island of Montreal. There were rapids there and so very early on, mills were built between the island of Montreal and Île de la Visitation—first for flour and then as part of an industrial complex, which remained in operation for a very long time. When the hydroelectric plant was built in the 1920s, it raised the water level of Rivière des Praries and some of the rapids disappeared, but there are still a few to the east of the plant.”

WHAT IT MEANS FOR THE CITY

“[The space] reminds us of the relationship between Montreal and the water that surrounds it. The water was used to power machines, then to produce electricity. But the space was given back to Montrealers. A large part of the park was reforested [and] nature is allowed to follow its own life cycle. A city is a place that’s built by human beings so that they can live and work and have homes, but also so that they can amuse themselves and relax—that’s all a part of what a city is.”

Lucien L’Allier Metro Station

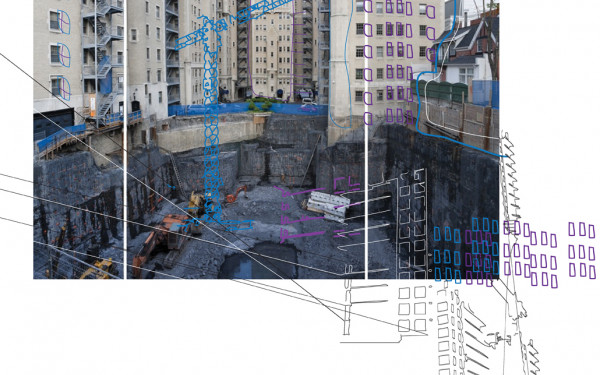

Howard Davies, Architect // Atelier Big City

WHY IT’S SPECIAL

“It’s very deep. The space is just on an epic scale. It’s really a celebration of transportation in the grand tradition, it’s almost like a cathedral. Isn’t it kind of unique that there’s really nothing there? It’s just the space, there’s no shops. It’s very pure, kind of contemplative. The brown brick and concrete is not what I’d consider to be the most spectacular kind of materiality, but in terms of its space, I think it’s really great.”

WHY THEY BUILT IT THAT WAY

“The station is deep by necessity, there was no other way to do it. Saint-Laurent metro is almost at the level of the street, it’s like one floor down. But this one is five or six floors down. The high ceilings were inevitable. It’s what you would call a lucky break. I suspect that is as close as they could get to put the platform. They said, ‘Okay, we have to get up six floors, so make it interesting.”

ITS POTENTIAL

“You have this metro station, you have a link to the Bell Centre, you have a commuter rail station and they all kind of overlap in an exciting but also incomplete way on the same site. For all the grandeur of Lucien-L’Allier, it’s waiting for the next step. If I was taking architects around I would say, ‘Yeah, look at this place-can you just imagine what’s gonna happen here, how the city’s gonna get this incredible project eventually?’”

AND…

“I think there was a party there once. Definitely a great place to have a party.”

These interviews have been condensed and edited.

_900_600_90.jpg)

_900_600_90.jpg)

WEB_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)