Wired for Good

New York Doctor Comes to Concordia, Argues That Biomechanics Makes Us Altruistic

If you saw someone slip off the metro platform and fall down onto the tracks, would you jump down and save them?

A New York man did exactly that back in 2007. When a complete stranger suffered a seizure and fell onto the subway tracks, Wesley Autrey jumped down and flattened his body so that the approaching train would pass over them. Not a scratch was left behind—just a bit of motor oil on the back of Autrey’s head.

That story is what inspired Dr. Donald Pfaff of the Rockefeller University to study the neuroscience behind altruism. With a background in biomechanics, Pfaff looked at the brain’s inherent functions to understand how they contribute to altruistic or aggressive behaviours.

His research leads him to argue that humans are naturally designed to be good to each other. Concordia’s Science College invited him to explain the theory behind his book, The Altruistic Brain, on March 31 at the Oscar Peterson Hall in the downtown Hall building.

“Historically, when we talk about good behaviour, [it has] been enforced by religion, by law, and by many other social and cultural forces,” said Pfaff. “What I’m trying to argue, as a neuroscientist, is that our brains were built to emit this kind of behaviour.”

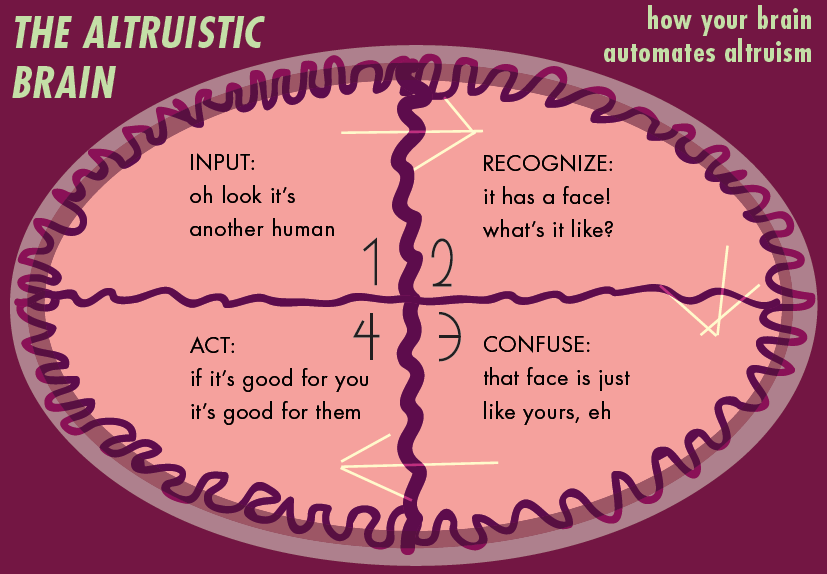

Pfaff’s altruistic brain theory says that if you’re going to do something for another person, your brain will process that act in a series of four steps.

First, the brain recognizes the target of your act, or whom you’re working for or against. Second, you’ll start thinking about that target by using the part of your brain that recognizes faces. The third step is where the brain blurs together the images of the other person and yourself.

“I’d like to point out that this third step, which is the main trick of the theory, is really easy,” said Pfaff. He argues that this occurs because it’s the simplest thing for the brain to do. Rather than work twice as hard to process both images of yourself and the other person, your brain would rather take the easy route and lose some information, mashing both images together. He said it’s easy to understand if you compare the brain to a computer.

“Is it simpler to improve a computer’s performance or to break it and make it worse? Clearly, it’s easier to make it worse,” he said.

By blurring the image of the person for whom you are doing the act, Pfaff explains, it’s easy to imagine that you are doing it for yourself. He argues that by placing yourself in the shoes of the other person, you are more likely to act altruistically. It’s the same logic that is behind “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

The final step is deciding whether you should do it. “Is that particular behaviour good for you?” asked Pfaff. “If it is, then it’s okay to do it for the target person. If it’s bad for you, don’t do it.”

Pfaff’s theory is accessible to anyone without neuroscience training. However, it’s counterintuitive nature and alleged oversimplifications have received criticism. One review of his book said that most of his evidence is collected only from inference and that the rules he outlines in his four steps are only theoretical possibilities.

In Pfaff’s lecture, he did point out that there were scattered differences among the data that he analyzed. He stressed, however, that those differences should not be ignored.

“The notion that we should cram everybody into an average, vanilla-flavoured social domain is a bad idea,” he said. “To have everybody be at the average would be the worst possible thing.”

1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

2web_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)