McGill Hosts Panel on Institutionalized Racism and the Post-Colonial State

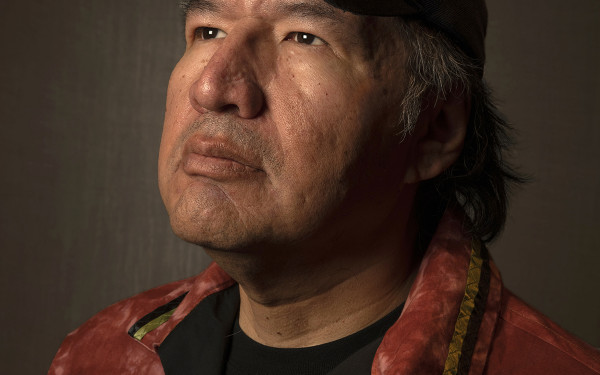

First Nations Speaker and Activist Kahn-Tineta Horn Led a Panel Talk

Is it too ‘kumbaya’ to muse that McGill University change its name to ‘The University for Advancement of World Peace?’

That was one idea that Kahn-Tineta Horn, a First Nations political activist, observed at a panel discussion at McGill on Thursday Nov. 5. The event was moderated by Sta Kuzviwanza, Student Society of McGill University’s (SSMU) Equity Commissioner, in association with several African student societies.

The talk made a connection between Canada’s colonial past and the institutionalized racism in South Africa, weaving together James McGill’s imperialist legacy with ongoing student movements in South Africa that challenge the lasting remnants of apartheid— Open Stellenbosch, Rhodes Must Fall, and Fees Must Fall.

“Universities can be laboratories for colonialism,” Horn said, in reference to McGill’s receival of a notice of seizure by the Mohawk community in September. The notice claimed that McGill not only violates the law of the land but also the Great Law of Peace.

Montreal is situated on traditional Kanien’kehá:ka, or Mohawk territory as part of Great Turtle Island.

“The entire country is built on our resources. The minerals, the oil the lumber. That’s all ours, we never gave any of it up,” she explained.

Horn was not the only one appealing for a peaceful decolonization of university spaces.

Also sitting on the panel was Rachel Sandwell, a post-doc scholar, historian of southern Africa, and specialist of race, gender, and the politics of resistance in South Africa. Her focus was on student movements in South Africa and how their goals compare with those of the Kanien’kehá:ka Mohawk community.

“To decolonize education, university curriculums must acknowledge that Canada is an ongoing settler-state,” she said.

Edwina Shaddick, a Sociology Masters student and attendee of the talk, spoke about Canada and South Africa’s shared colonial past.

“In the 1920s, South Africa consulted Canada’s policies on the Aboriginals and was encouraged by Canada’s residential school system,” she explained.

From this common past stems two distinct movements: Aboriginals reclaiming their land rights and black students in South Africa seeking more inclusion, particularly at the University of Stellenbosch. Their common ground: decolonizing education.

Kuzviwanza led her panellists to discuss how students should confront decolonization on campus.

Sandwell, having been in South Africa in mid-October, witnessed firsthand the race relations among the privileged white Afrikaans and the marginalized Black students.

“The Fees Must Fall Movement was totally peaceful. The students were amazing. I was there,” said Sandwell.

But it’s not only about tuition or the financial inaccessibility of education. Black students at Stellenbosch have been challenging the role of the university for using language that excludes them, as well as a curriculum that under-represents the diversity of cultures. They are also calling for the recognition of Stellenbosch’s role in the Apartheid.

Within two weeks of the South African demonstrations, the president of the country met with student leaders to negotiate their needs.

“These students took back the university by symbolically renaming buildings, rejecting colonial names, recreating africanist names, recreating pre-settler state names,” she said.

Sandwell showed how reclaiming the names and legacies of African historical figures and removing symbols of colonialism means the university can “become a site for generating knowledge about resistance.

“The university can have a vanguard role in pushing for such social changes,” she said.

Language and media play a key role in the success of such a movement. And yet the publicity of the state tends to misconstrue such solidarity efforts by using language that denies and delegitimizes, she explained.

“Protests are often labeled as violent. Even the word protest is used as a scary word,” said Sandwell. “Showing non-violent disagreement is not a protest, it’s a demonstration.”

Although remnants of apartheid still exist in South Africa, Sandwell takes a hopeful approach.

“Students are what the university is. The university can pretend it’s a whole lot of other things, but students form the core of the university,” she said.

Both panellists linked Demilitarize McGill as an exemplary student effort to push for social changes and to take back their universities peacefully.

According to the panelists, decolonizing education means that student interventions can change academic curriculums to be more inclusive, less eurocentric, and can acknowledge the history of a land.

“Learn the law of the land, learn to think differently and learn to help each other,” concluded Horn.

In an informal Q&A period, one student still wanted to know precisely what initiative can create such peaceful recognition for Aboriginal land.

Horn, with the same distinct optimism she held throughout the discussion, smiled once more and replied, “It’s not my job to think for you.’‘

Correction: In a previous iteration of this story, it incorrectly stated that Kanien’kehá:ka is outside Montreal. In addition, Edwina Shaddick’s name was previously misspelled. The Link regrets the error.

_900_675_90.jpg)