Land, Love and the Colonized

Indigenous Artist, Academic and Activist Talks Decolonial Love

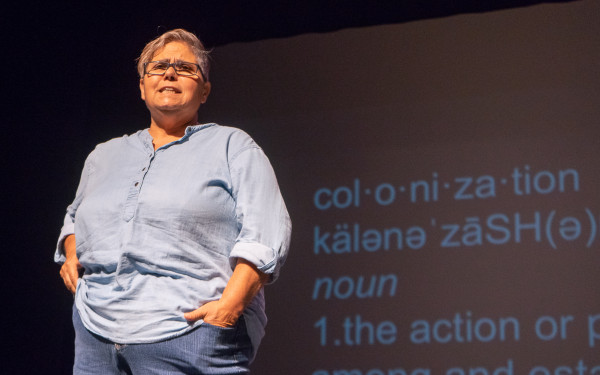

Self-described “recovering academic” Leanne Betasamosake Simpson wove traditional Anishinaabeg stories about trust, racism and confidence together with narratives of Western education in a thought-provoking reading at First Voices Week.

Editor of The Winter We Danced, a collection of essays, stories and poems about the Idle No More movement and Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back, a collection of Anishinaabeg traditional stories and meditations on Indigenous intellectual movements, her latest work is Islands of Decolonial Love.

Simpson read excerpts from Islands to an audience of Concordia students on Jan. 29 as part of the First Voices week at Concordia.

Identifying herself as an artist, academic and activist, Simpson said that she has a problem with the boundaries between these roles and declares that, “for me, they don’t exist.”

Simpson, who is of Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg ancestry and a member of Alderville First Nation, told four stories that painted connections between land, bodies and stories and showed her audience a way of thinking that juxtaposes traditional Western education systems with indigenous culture.

Her first story was about an ikwezens [girl] who discovers how to extract maple sugar by copying a squirrel and shows her mother and aunties what she has found. Helped by her community but confident in her own curiosity, the ikwezens learns to trust herself.

The ikwezens is supposed to be there out in the forest learning and playing, something that Simpson made a point of emphasizing. Simpson hailed it one of her favourite stories because “nothing violent happens” and it presents a counter-narrative to the hundreds of cases of missing and murdered Aboriginal women throughout Canada.

After her story Simpson asked the following questions: “What if the ikwezens had been in an educational context in which having an open heart was a liability instead of a gift? What if she hadn’t been on the land at all? What if she lived in a world where no one listened to girls? Or where she had been missing or murdered before she ever made it out to the sugarbush? What then?”

Simpson described driving in the early morning from Peterborough, Ontario to Toronto and looking at the highway thinking about whether her great-great-grandmother would recognize the land that they have shared. The forces of colonial power have tried to remove Aboriginal people from their connections, first to land but also to history and, she argues, intimacy.

Addressing her own hopes for future Aboriginal populations, Simpson said, “I want my great-great-grandchildren to be able to fall in love with every piece of our territory.” She wants them to live without fear, to value their responsibilities to the land and to be heard and cherished during their lives.

Simpson’s last story was the retelling of her daughter’s first experience with racism. A man confronted her and her daughter while they were picking wild leeks in the forest. Her daughter shut down about the experience and Simpson looked for help from female elders in the community.

Simpson’s friend Tara Williamson, a singer-songwriter, suggested that Simpson herself needed to deal with the incident in order to help her daughter. Simpson ended up writing a poem about the experience, with Williamson collaborating with a musical accompaniment to produce the song “Leeks.”

When they recorded a video to accompany the song, Simpson’s daughter danced for it in the same forest of the encounter. Telling this story drew together themes of motherly love, community strength and her daughter’s power for the author.

During the question period following her talk, one person asked about her feelings towards reconciliation, a popular viewpoint towards healing relationships between settler colonial and Aboriginal populations.

While acknowledging that initiatives such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in British Columbia have helped some survivors of residential schools, she pointed out that the these commissions do not talk enough about the relationship between land and bodies and that the conversation about missing and murdered Aboriginal women has to be at the forefront of these discussions.

In response to another question about how descendants of colonial families can join the conversation, Simpson stated, “We need more communities of resistance against the current system” and added the necessity of teaching people to be able to think within the indigenous intelligence system.

For more information about Leanne Simpson, visit http://arpbooks.org/books/detail/islands-of-decolonial-love

Video by Evgenia Choros

web_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)