Curing Concordia’s Inaccessibility

CURE’s Audit-a-Thon Aims to Create an Inclusive Environment for All Students

Paul Tshuma will be graduating from Concordia University at the end of this semester.

The music student, like many soon-to-be grads, is preparing to join the workforce as his time at the university comes to close. His time at the school, however, hasn’t been as typical.

Tshuma uses a motorized wheelchair to move around campus. On top of worrying about whether he’d be accepted into the classes of his choice, he also had to consider whether he’d be able to physically access the classrooms.

Tshuma was one of a dozen students present at the Community-University Research Exchange’s Radical Accessibility Audit-a-Thon at Concordia on March 31 and McGill on April 1.

CURE, a new fee-levy group at Concordia, organized the event in conjunction with Accessibilize Montreal and with support from Quebec Public Interest Research Group Concordia and the Concordia Student Union to promote an inclusive look at accessibility.

“This Audit-a-Thon was in support of a larger project called the Radical Accessibility Audit Project,” explained Cassie Smith, CURE Concordia coordinator. “It’s a crowd sourcing initiative to collect comprehensive accessibility information on different public venues around the city.”

The event at Concordia in particular, Smith said, was meant to address the issues present within the physical spaces of the university that able-bodied students might not take note of.

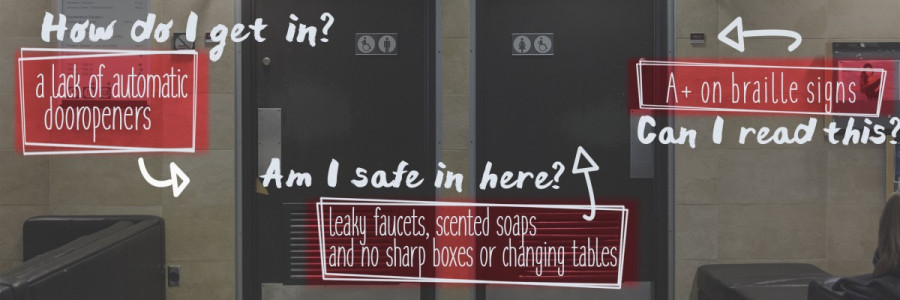

“Even though Concordia seems accessible, it goes beyond ‘Is there an elevator in the building?’ There are a lot of things that able-bodied people don’t think about,” said Smith.

For example, she noted, the free telephones on the seventh floor of the Hall building downtown are placed at a height that is inaccessible to those in wheelchairs or who “get around at a lower height.”

Tshuma mentioned that a roadblock he faces includes the many doors that do not have automatic buttons.

“I see no point in there being those [heavy glass doors] if they’re always going to be shut,” he said. “They don’t have any automatic door openers. Those things need to be addressed.“

Inclusivity is one the main facets of the project. Tshuma said that it is this mindset that makes all the difference. “They are getting the information from a person with disabilities, to really understand what [the needs of students with disabilities] are,” he said. “I find when you don’t have that need, you cannot relate to the person who needs those services.”

By facilitating activities like these, Smith said that they hope to make sharing accessibility information easier for the general public, so that no one is left wondering whether they can attend an event.

“There are seven pages to this audit. It’s everything from wheelchair access, to if there are Braille signs to if there are gender-neutral washrooms,” she explained. “Its really encouraging people to think about accessibility in a holistic way but then also providing them with a tool they can use.”

For both Tshuma and Smith, creating an accessible environment goes beyond creating a physically inviting space. It’s about inspiring thought in those who are not directly affected by disabilities.

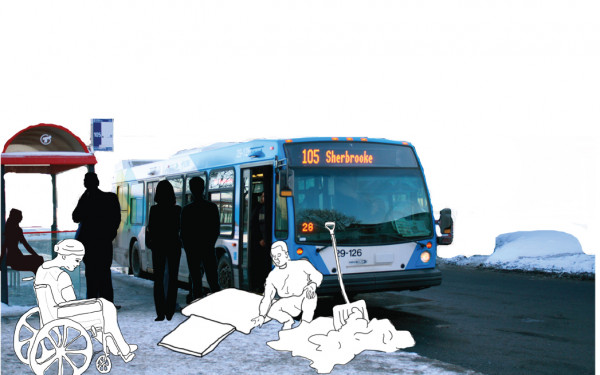

“Concordia students in the music department usually have events where they play outside the university,” explained Tshuma. “For me to [attend], even if I wanted to, it’s not possible because it’s not accessible.” He continued, “It’s more exclusive. For it to be inclusive, we need to get a venue that is accessible for everybody, you know? It’s not their first priority.”

A map of locations that have been audited is available on CURE’s website

along with an audit template.

Correction: A previous iteration of this article used ableist language that didn’t properly represent the story or subject of it. The Link regrets the error.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)