Collect ‘Em All

The Obsessive World of Collectors

Most people put their Pokémon cards in a drawer, never to see the light of day again. Others end up waiting for Hall & Oates outside a concert venue, hoping to add a little ‘rock and soul’ to their autograph stockpile. For lifelong collectors, it’s a thin line between hobby and way of life.

Existing in a universe completely unlike our own, celebrities live more than just the high life—the real perk is the constant ego boost that comes from the knowledge that people you will never meet care about the minutiae of your existence (proof: scan Kanye West’s Twitter account).

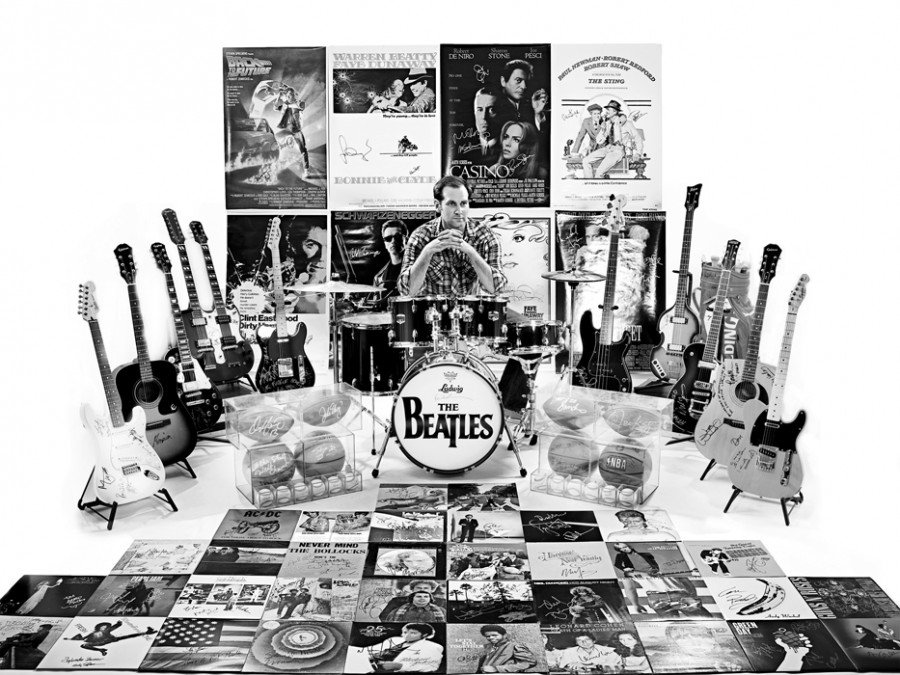

For years, the cult of celebrity has manifested itself in the pursuit of autographs. Bryan Ulrich, the operator of thesignaturelibrary.com, has managed to turn that pursuit into an art form, passion and business.

“I got into it as a hobby, as somebody who appreciates and admires and reveres people with talent and who make contributions to pop culture,” he said. “I’ve never been about chasing autographs for the sake of autographs. It’s always been about their story and their adventure in life.”

Ulrich, a native of Toronto, sells items that range from posters and albums to guitars and clothing—each emblazoned with the autograph of the celebrity connected to them, and each signature having been personally obtained.

On the site, Ulrich can be seen with his arm around almost every major figure from sports, music and film from the past three decades, but none is more striking than a photo of a smiling Ulrich standing next to a masked Michael Jackson. The two shared a symbiotic relationship in the last year of the pop star’s life, which has resulted in Ulrich possessing the single largest collection of Jackson signatures in the world.

“I cultivated a relationship with him pretty quickly. He was very cool to be around, and super-generous,” said Ulrich. “He collected his own memorabilia, so he would get stuff from me—weird stuff, or posters he had never seen of himself. I’d give him 30 or 40 things in one shot and he’d sign 20 or 30 and keep ten.”

As part of his business, Ulrich does take requests—he even tracked down Miley Cyrus for personalized happy birthday wishes for a customer’s daughters once—but he does have rules. He claims he will only get the signature of people he considers culturally important and interesting.

“If somebody asked me for Justin Bieber’s signature, well, it’s not something that I’d like to do,” he said.

Bugger Off

While the Kirk Douglas-signed Spartacus photo from Ulrich’s website may seem dated, it pales next to the objects in former Concordia professor Mark Bourrie’s possession.

Bourrie, a reporter on Capitol Hill in Ottawa, collects something far creepier than the politicians he deals with: trilobites, or fossilized bugs that are older than dinosaurs.

Although he does have specimens in his collection that are valued at up to $20,000, the big part of why he got trilobite-fever is simple: they’re neat.

“I started collecting them ‘cuz I thought they were cool. I liked that they had eyes—they looked like an animal,” he recalled. “And they’re so old. When you put a bunch of them [next to each other] and look at them, you can really see the diversity of creatures when the world was so different. You might as well be looking at alien life forms.”

Despite the financial benefits that would come from dealing his trilobites, Bourrie is not ready to sell.

“I save just about everything I find,” he said. “I’d like to keep it all together, I’d hate to see it all sold here and there.”

Finding Value

Beyond sentiment and money, psychologist Corinne Rowniak believes that there are several competing motives behind stockpiling objects, no matter what they are.

“It can be a kind of making memories,” she said. “Sometimes, when people create collections, each item represents a time and a place. When the objects have more value, there’s a self-aggrandizement. They become important by acquiring something that’s worth a lot, as opposed to a collection like bottle caps.”

Robert Cresthol, a dealer in baseball memorabilia who also maintains a private collection, admitted that nostalgia is part of the reason he updates his stash.“Baseball history is very colourful,” he explained. “There’s a lot of baseball purists that get more of a thrill out of the world of baseball in the past, then the present day game, which is tarnished by steroids and spoiled, rude athletes.”

The element of nostalgia in building a collection is one Bourrie agrees with. His collection was largely built not by buying and trading pieces, but by searching for fossils in areas undergoing excavation, and he can recall where he found most of the specimens in his collection. The thrill of the chase, he said, is the element to collecting that’s powerful.

“I think [finding a good specimen] is like winning something in a lottery or casino,” he said. “It’s a total rush. I can see how it would be addictive to win something. I should probably stay out of casinos,” he added with a chuckle.

If that kind of rush seems dangerous, Rowniak says it’s actually benign – as long as that passion doesn’t turn to obsession. While compiling a large amount of slightly different objects might seem like a strange hobby to some people, it can actually indicate a healthy thirst for knowledge – albeit in a fairly limited field. Think of it as a mildly eccentric way of connecting to others, and that can’t be bad—even if that involves hanging out with Hall & Oates.

This article originally appeared in Volume 31, Issue 03, published August 31, 2010.