“Call Me Iggy”

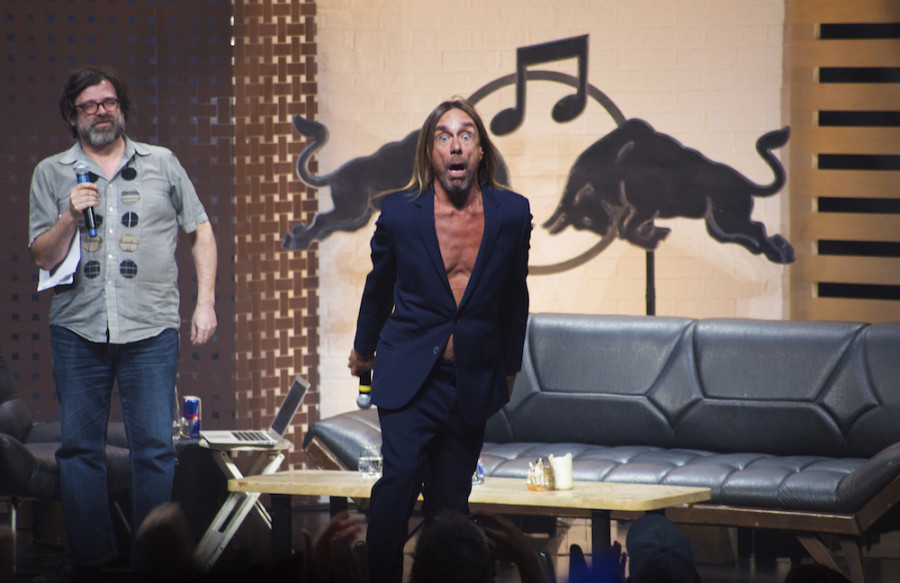

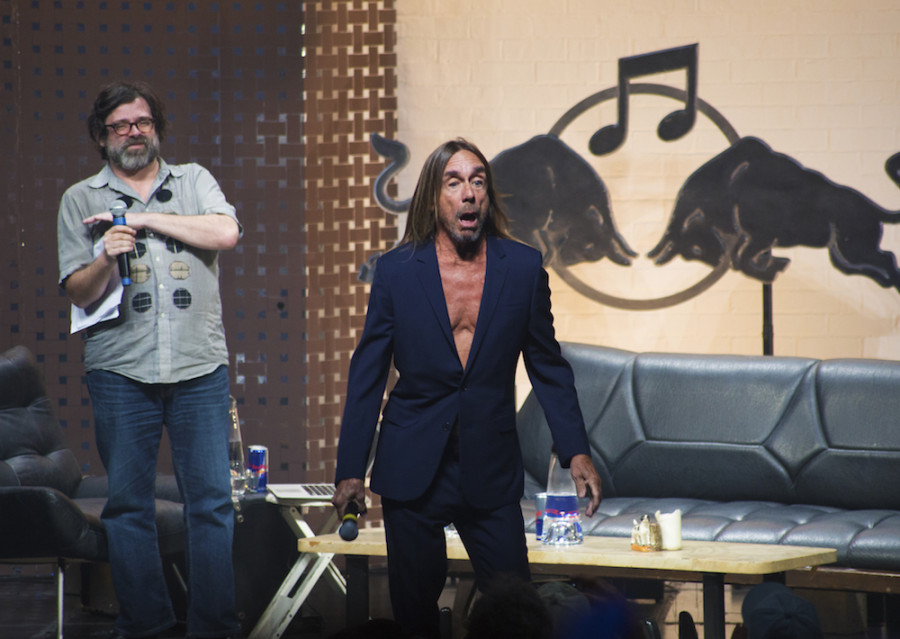

Punk Legend Iggy Pop Speaks at Red Bull Music Academy

Boisterously, a human firecracker exploded onto the scene, sparking the crowd out of their seats. He is called the “Godfather of punk,” and dubbed “the world’s original forgotten boy” by some. Others just call him James Newell Osterberg.

“Call me Iggy,” he said.

Far from being dilapidated, Canada’s oldest theatre, Ludger-Duvernay—complete with red velvet seats, a curved balcony delineated with classic black rod iron, and its ceiling covered in hand painted fleurs-de-lis—served as the venue for the 69-year-old punk-hero to have a conversation with music journalist, Carl Wilson, on Sept. 26.

Despite Iggy’s recent projects, such as his new album, Post Punk Depression, or American director Jim Jarmusch’s new Stooges documentary, Gimme Danger, the conversation wasn’t used as a promotional springboard. Iggy’s off-kilter conversation as part of The Red Bull Music Academy revealed why he prefers being shirtless, and delved into his views on the notion of the American Hero.

Juvenile Blues

It was growing up in a trailer park— “but a nice trailer camp,” Iggy quickly clarified—situated in a high-end school district, that helped young Iggy develop such a particular ill-will towards the norm.

Iggy recalled how his high school experience put a chip on his shoulder. “It made me want to to succeed in the same world as the guy with a house in bourgeois neighborhood—but I didn’t want to be a fucking bourgeois!” He exclaimed.

At certain points, Iggy seemed to be lost in recollections, recanting stories of how a topless picture of Charlotte Moorman embracing the cello left a big impression him. But Iggy shared malleable stories— they stretched out of shape, but never broke away from the answer.

Drawing upon his time in the High School debate team, Iggy emphatically declared that “you can articulate anything,” his eyes peering out of their sockets. Indeed, the John Cage affiliate, Mormon, influenced Iggy to play a vacuum cleaner or a blender as musical instruments. Iggy added that when “you take off the head [of the vacuum], you can make it sound like a whistling wind,” or make the blender sound “like Niagara falls.”

Indeed, anything can be articulated to meet artistic ends.

“You can articulate anything” —Iggy Pop

Lost in a Shirt: Loneliness and the American Valhalla

“Will he be wearing a shirt?!” The quintessential Iggy-question led Wilson to ask. “There’s not a lot of guys, or men, who make such a poignant display of their body,” he said.

Iggy darts in. “The Pharaoh! The Pharaoh in Egypt never wore a shirt. That’s where I got it,” he explained, solemnly adding, “I get lost in a shirt.”

Wilson commented that in Western Pop Culture, such displays of the body are “much more associated with women.”

“Well, I like being feminine,” quipped Iggy.

In his new 2016 album Post Pop Depression, the song “American Valhalla” ends by repeating the line “I’m not the man with everything, I’ve nothing, but my name.”

“Is there an essential loneliness to being Iggy Pop?” Wilson asked after playing the track.

Iggy answered after a pause. “Yeah, but I also have great aspects to my life—a lot of rewards and happiness to it.”

After “duking it out” with New York City for twenty years Iggy explained that he went to live out his “afterlife” in Miami, Florida. “I’d like to get out at the beach, it’s the end of all the crap—no judgment system, no visible rule, no skyscrapers, no slums, no traffic lights […] no stuff! It calmed me down.”

For Iggy, it’s where the ocean meets the skies that spark the question: “Is there an American Valhalla?”

In Norse mythology, the Valhalla is a great hall that receives war heroes after their death. Whereas, the return home for American soldiers is far from great: it is close to death—a plastic afterlife.

“What is the reward for these people besides a bed in a hospital and oxycontin, or a weekend in Vegas?” Iggy said that these soldiers are deemed as heroes, but judged by “ten people over there who think that you are a hero, and twenty people over there who think your heroic situation should have never been allowed.”

It is within these complicated nuances of the idea of American hero, that Iggy relates to the lost afterlife of these soldiers. “There are times in life when you hit this spot, where you say, ‘I don’t have any plans, I don’t know anything’… and you’re looking … I suppose for some sort of paradise that doesn’t exist.”