The Unscience of Sleep

Nothing What It Seems in Hall’s Certainty Dream

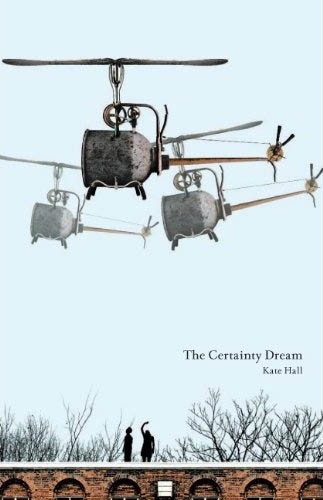

Kate Hall’s poetry collection The Certainty Dream, which won her the 2010 Quebec Writers Federation’s A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry on Nov. 23, is a strange beast.

Though there is little from Hall or the people in her poems to suggest that all the poems are actually dream poems—poems whose narratives take place within a dreamscape, real or imagined—that seems to be the point. We never seem to know we’re dreaming until later, upon awakening, and considering the dream in retrospect.

Hall’s poems work much in the same way. They often seem vague and incomprehensible at first glance, but later on, it is hard not to believe there is a strange, nigh inscrutable logic at work behind the words.

This is an approach that may be jarring and even grating to some readers, but, if you’re the type to be reading a poetry collection in the first place, you really have no excuse not to stick it out. Poetry is the dream to fiction’s waking life—short, hard to grasp, everything magnified and all significance at once more and less important than it should be, and perhaps that is why, out of context, many of these poems could even pass for non-dream poems.

As they add up, however, the continuing absence of the real becomes damning. The more one reads of The Certainty Dream, the more one becomes certain of being trapped in a dream world. This makes navigating the poems both easier and slightly less interesting, however, as the process by which every physical object, every interaction that goes on loses its reality also lowers the stakes on everything.

Why, one might ask, should I care about someone else’s dream-poem, if I wouldn’t even care about their dream? There is already a fairly culturally ingrained tedium associated with listening to other people talk about their dreams. How could a dream-poem collection sidestep this?

Hall’s answer is in providing the reader with something that must be experienced for oneself. It is one thing to hear about her capacity to effortlessly render that strange dreamlike confusion, but unless you actually read these poems, the impressiveness will not translate. To read these poems is to be caught in a dream; to read this collection is to be caught in a series of them. That they are not your dreams makes them all the more alienating and frustrating. Hall has re-imagined Richard Linklater’s 2001 rotoscoped masterpiece Waking Life as poetry, and the results are similarly frustrating, exhilarating, confusing and thought-provoking.

This is a book that will certainly prove challenging to the average reader—perhaps even to the average reader of poetry. Nevertheless, it is impossible to deny Hall’s talent for marrying concrete language and action with the absurdity and vague narrativelessness of dream, the same way dreams are built with the blocks of our waking lives.

In the poem “Insomnia,” Hall poses this hypothetical situation: “If I were to sleep, I’d sleep on an iron bed.” If you’re going to sleep, however, don’t sleep on The Certainty Dream. This one is worth having.

This article originally appeared in Volume 31, Issue 17, published January 4, 2011.

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)