Invisible on Campus

Rape Survivors and Sexual Assault Centres

Nearly a quarter of female university students will have experienced a sexual assault by the time they graduate.

That’s a shocking, horrifying statistic and coupled with Concordia’s culture of social awareness and responsibility, it makes the oversight of these statistics even more unsettling than when they’re ignored in mainstream society.

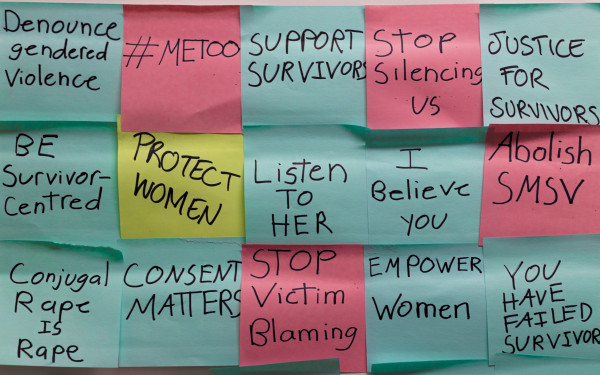

“It’s pretty clear that universities are a place where a lot of sketchy stuff goes down,” said Maya Rolbin-Ghanie, a 2110 Centre for Gender Advocacy campaigner. “The anti-sexual assault campaigns that I’ve seen are generally pretty flawed and target the victim as someone who needs to change their behavior.”

The 2110 has been working since the fall of 2011 to found a sexual assault centre on campus. The university’s position is that there aren’t enough resources for it and that health services offers sufficient aid to assault survivors.

“We don’t have one because if someone comes in after being sexually assaulted then we refer [them elsewhere],” said Julie Gagné, the manager of Clinical Services at Concordia. “We would never turn someone away, but by law it has to be done at certain places so the [perpetrator] can’t deny it in court.”

If they want the rape exam, the university sends students to the CLSC Faubourg or Montreal General Hospital, where they can also book a counseling appointment—but due to demand, they could wait over a month to speak to someone.

For advocates of a sexual assault centre on campus, health services just isn’t specialized enough to address the needs of survivors in a timely and sensitive way.

“An actual sexual assault centre with people trained to deal with sexual assault, non-consensual sex—and that would cover things like rape kits—[is needed],” said Rolbin-Ghanie. “But also to help people navigate the legal system and their legal options on top of medical ones.”

Rolbin-Ghanie added that advocacy is another reason to have a specialized centre, because the stigma surrounding assaults keeps victims invisible. The idea that the survivors brought the assault on themselves is a prominent part of most anti-assault campaigns.

The status of this misconception became obvious last year when a Toronto police officer giving a campus safety information session said that if women wanted to stay safe “they should avoid dressing like sluts.”

This statement is seen as being responsible for the controversial “slut walk” demonstrations that sprung up across North America following his remarks.

This same caricature of sexual assault is echoed at Concordia. The university’s security webpage advises that, to prevent assaults, women should avoid dimly lit areas and not consume alcohol to the point that they can’t “react quickly to any situation.”

“They address people that might be assaulted but they don’t address people who assault,” Rolbin-Ghanie said. “A society where that is the primary message in the campaigns is just an indication that we still have values that are kind of sick.”

According to a Canadian study, one in five male college students surveyed said that forced intercourse was alright “if he spent money on her,” “if he is stoned or drunk,” or “if they had been dating for a long time.”

Concordia’s approach to outsourcing sexual assault cases is reinforced by the idea that a special centre for survivors on campus would be counterproductive.

“Most of the time people would not join a group in their own environment,” Gagné said, “because they would see people they see everyday within the building. Usually support groups are on the outside so people don’t know each other.”

The 2110 has the goal of collecting 5,000 signatures for their cause to both raise the profile of the issue and put pressure on the administration. On March 5, the signature-collecting campaign was taken to the Hall Building and volunteers talked to several hundred students.

“The vast majority of people are willing to sign [the petition],” Rolbin-Ghanie said. “And most students are quite shocked that there’s not a sexual assault centre, most of them just assume there is.”

—with files from Catlin Spencer

7_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

5_2_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)